It is not my intention tonight to speak of South African Missions generally, but specially of the mission to Bechucialand. Before beginning this story, however, I should like to say a little about our older Mission Station, Thaba 'Nchu, from which the BecOnaland Mission was an offshoot - for the natives at Thaba 'Nchu are a branch of the great Bechuana nation.

Thaba' Nchu is a large and important native town about 30 miles from Bloemfontein; it was the residence of an independent chief name Moroka, whose country joined the Orange Free State. Our mission there had been established over 40 years and two missionaries were stationed there. The Rev James Scott was the super at the time which I speak, and my father, the Rev Jonathan Webb, was his colleague. The town spread along one side of a river, and on the other side were the houses of the missionaries, our chapel, and two houses occupied by traders. The Church of England also had a mission and church there. In the vicinity rises a large mountain; the dark colour of the rocks which form it, and the scanty vegetation, obtained for it the name of Thaba 'Nchu, Mount Black. This mountain gave the town its name.

Our chapel was built of stone; inside the rafters of the roof were all visible, for there was no ceiling; the floor was of earth, beaten down and hardened. The pulpit was placed at one side. It was a large building and was used on week days as a school. On Sundays a row of forms was placed round the pulpit, and the floor in front of them covered with grass mats of native manufacture. One form was reserved for the chief and his attendants, or members of his family - Moroka frequently attended the Services. The other seats were for the Missionaries' wives and families and for any other white people who might chance to come. The rest of the space was given up to the Bechuana, who came in and squatted on the floor where they pleased; they were orderly, however, those who arrived first sat as near as possible to the forms, and those who followed sat as near as they could - there was no demand for back seats, late corners were welcome to them. The women invariably sat on the floor, a few brought mats; some of the men brought little stools made of wood roughly shaped, with thongs of raw hide stretched across to form the seat. Many a time the chapel was packed to the door and people stood outside to hear what they could.

The members were carefully trained in Methodism as it used to be; Class meetings; Love Feasts, and Fast Days, were regularly observed. Love Feasts were held in the afternoon. Mrs Scott and my mother took turns to provide buns for the feast; these were of fair size, slightly sweetened, and a few currants added. They were carried in on trays, and placed in the pulpit, also several buckets of water, and a lot of small basins, such as are used by Boers and natives instead of cups. I cannot tell you* the number of members, but it was large, and all came who possibly could. I wish I could make you see that scene as I recall it; though only a child of 5 or 6 it made an impression which has never faded. The eager, expectant faces of the people through the opening portions of the service, the hearty singing and fervent responses. But the climax was reached when the buns were handed round. Each member received a whole bun and a basin of water. And how they enjoyed those buns! A school boy with a large slice of wedding cake could not have felt more satisfaction. Some ate with their eyes closed, the better to enjoy the taste. This part of the feast was soon over. Then followed the experiences, and there was no waiting, many were eager to speak of the great things God had done for them. It was to them indeed, a Feast of Love.

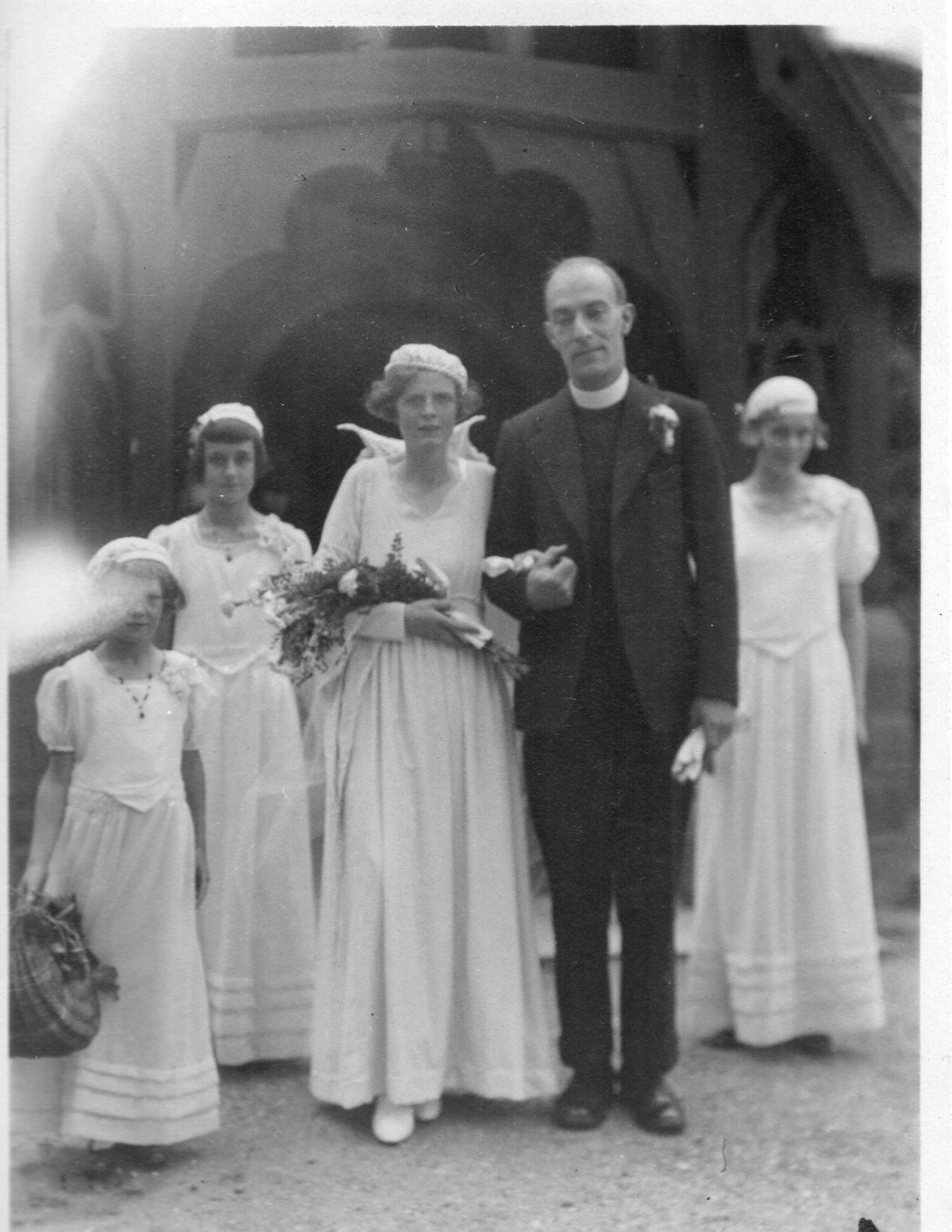

A Native wedding was a curious mixture of civilization and barbarism; the Xtian families did their best to follow European customs on these occasions. A maid-servant of my Mother's was married at Thaba 'Nchu; she was a plump good natured girl, named Annie. A few weeks before the wedding she went into Bloemfontein, and there purchased a piece of pretty blue material for her wedding dress. Of course there was no dressmaker in Thaba 'Nchu, so she came to her former mistress and begged her to make the dress. This my mother did, turning out a nice dress, and the girl was well pleased. About a week before the wedding the bridegroom elect went to Bloemfontein to make purchases; there he saw a white muslin with a pattern of black leaves. This took his fancy; he bought some and presented it to Annie, asking her to make it her wedding dress. Again she came to my mother for help, but my mother was not very willing to undertake the fresh task. She had no sewing machine, and five little girls of her own to sew for, so she had little leisure. She tried to persuade the girl to be content with the blue dress, but all in vain. There was no one else to whom she could send the girl, and unwilling to grieve her, she kindly promised to make the dress, and Annie was happy once more. The couple being members were married in the chapelithe bride in her white and black muslin, 'and a white straw hat with gay trimmings; the bridegroom m ordinary European dress. Many of the friends were in native dress, a gaily coloured blanket slung across the shoulders, or a kaross of sheep skin, with many strings of bright beads around neck, arms, and ankles.

When the ceremony was over, the bridal party formed a procession and marched all around the town singing. You know that old round, Come follow, follow? Well, they sang that to the same air as we do, and on this occasion they sang 'To the wedding' instead of 'to the greenwood'. (Those-are-the Bechuana-wortleia—etc) After about two hours marching and singing, the party repaired to their but where a feast was prepared. The chief item on the bill of fare was beef. An ox is killed, the flesh well stewed with the bones and marrow, so that it makes a very rich food, and on this the guests regale themselves. Of bread and cakes they know nothing. Their ordinary food is a very thick porridge made of kafir corn meal - kafir corn is a sort of millet - when this fails they use maize meal. With this they take milk, sometimes fresh, but more often thick and sour. Meat is a rare luxury, so it is all the more appreciated when they can have their fill at a wedding. The preparations are extremely simple. The guests are received in the large circular enclosure which surrounds each hut; they seat themselves on the ground in a circle; seats of honour are provided for bride and bridegroom, these may be camp stools, or the family may have attained to the dignity of chairs. Some of the three- legged pots in which the stew has been cooked are carried into the centre of the circle, the stew is served out with wooden ladles, into small wooden bowls, and eaten with wooden spoons. No one is at all concerned it the supply of spoon comes short - fingers will do instead. Feasting and singing continue all through the afternoon, and often late in the evening. These are the general proceedings at a Christian wedding. At a heathen wedding much native beer is consumed, with the usual result - intoxication, and wild, unrestrained revelry.

Among the many trials which befall a missionary's wife, one occasionally has a humorous side which is seen when the painful part has passed away. Such was the incident which I shall now relate. The chief, Moroka, was very friendly with our missionaries, and frequently visited them in their homes. These visits were quite without ceremony, the only attendant on the chief being an old man. Moroka was never seen abroad without this man, who had a habit of walking close behind his lord, this earned for him the name of 'the Chief's Shadow', and he was seldom called by any other. This old man had taken a great fancy to my mother's tea-cosy; it was of bright red cashmere, with a pattern braided in black - that was the fancy work of those days - and it was thickly wadded, and lined with flannel. He thought it would make an excellent cap, and, not being bashful he asked for it more than once, but wa, refused. My mother valued it as the work of her sister; it was the only one she had, and it could not be replaced in that uncivilized country.

She had several times put it out of sight when the chief and his shadow were seen approaching; but one day they came, and the cosy stood on the sideboard. After greeting the chief, my mother left the room to prepare coffee for her guests. Coffee, with cake or bread were always offered, and never refused; indeed, the chief used to accept the whole plate of cake, give a piece to his shadow, and eat the rest himself. The chief ate talking to my father, while his shadow feasted his eyes on the coveted cosy. Imagine my mother's feelings, when, on entering the room again, she saw the Chief's Shadow sitting with ha tea cosy on his head! In no way abashed, he laughed, and told her it fitted him well, would she give it to him? This time his request was granted, for my mother had no desire to put that tea-cosy on her tea-pot again - and you would not wonder if you knew the habits of these people. So the tea cosy became a cap, and the old man walked proudly out wearing it. I don't know how he stood that thick wadding after being accustomed to a bare head, but vanity is the same in a Mochuana as in an Englishman, and his vanity enabled him to bear the discomfort; when we left Thaba 'Nchu he still wore a faded dirty cap, which had once been a bright, pretty tea-cosy.

In the year 1870 the Missionary Society resolved to send a Missionary to Moshaneng, to visit the people, and bring back a report. My father was chosen for that work, and he decided to take with him his wife and four little girls, the eldest of whom was 8 years and the youngest 18 months; of these I was the second in age. My Father's sister, who was staying with us at the time, also accompanied us. The journey had to be taken in a bullock wagon, and the whole trip was expected to occupy three month. It was a serious undertaking - Moshaneng was over 300 miles away in the interior, in that part of Bechuanaland which borders on the Khalahari Desert, and the way lay through wild, unoccupied country, with heft, and there, at long intervals, a homestead belonging to Boers of the poorer class. Supplies for 3 months had to be carried in the wagon, and as much baking as possible was done in advance. Rusks were made in large quantities, as they keep for months. Rock buns, small biscuits and cakes also were prepared. Butter and eggs were fairly plentiful and cheap, and could be freely used but sugar, currants, etc had to be used sparingly.

The wagon was an ordinary tent wagon, about 18ft long by 5ft wide, and was provided with a front box and a back box, these boxes are fitted to the wagon and used to pack provisions and crockery for daily use; on the front the driver sits. Inside there was a kartel - this is a frame of wood with thongs of raw hide stretched across and interlaced - a sort of bedstead. It was about 6 ft long, fitted to the wagon from side to side, and secured in its place by strong thongs at each corner. On this the bedding was placed. Under the kartel was a space about the same as under a bedstead; here were stored the flour bags, and other dry provisions, also the boxes of clothing. Between the kartel and the back box was an empty space, about 6 ft by 5 ft. At night this was a second bedroom, screened from the other by a curtain, and the bed made on the floor of the wagon. This bedding was rolled up in the day time. In wet weather this space was the dining room, indeed it served many purposes.

On each side of the wagon was a long row of canvas pockets, called side bags, these were a great convenience; in one the combs and brushes were kept; in another towels and soap; sewing materials also had a place, and one was always supplied with cakes or biscuits to give to the children, when they grew hungry during the long treks of 4 or 5 hours; narrow pockets at the ends, held each a quart bottle, in which the milk was carried - when there was any - and water for drinking. The outside of the wagon was fitted with a small box on one side, in which the extra gear for the oxen was kept; on iron hooks underneath the water barrels and buckets were hung, and in the space under the back of the wagon, between the wheels, a large carrier was hung by chains, this is called a 'trap', a shallow packing case was secured to it, where the saucepans, kettle, etc and a store of fuel were packed. I have described the wagon at some length, that you may have some idea of the capacity of these vehicles. They have no springs, and jolt a great deal even on good road; but no springs would stand the rough, unbroken country which has to be traversed. A gun and ammunition were a necessity, not for offensive purposes, but in hope of keeping the larder fairly stocked.

All being ready, a start was made; beside the 7 I have mentioned, who might be called inside passengers, there were the driver and leader, native men. The driver's name was Mokiva, he was a careful trustworthy man, and a good Christian. We were soon in a country teeming with game. Myriads of springbok were seen every day browsing on the plains; as they moved slowly along feeding, numbers of them were constantly leaping high in the air, over the backs of their fellows, covering yards in their spring. When startled they fled like the wind, and nearly half of them seemed to be in the air, so often and so rapidly did they spring. It was a sight not to be forgotten. Buffalo, wildebeest, hartebeest, zebras were common sights; zebras were easily alarmed, and we seldom got near them , but I remember several times seeing large herds scudding away over the veldt. Giraffes, too, were very timid, but occasionally we caught glimpses of them, their long necks stretched up among the foliage of the camel-thorn - their favourite food.

One day three lions were seen devouring a quagga; they were less than a quarter of a mile away, but did not observe us; so the wagon was quietly turned, and a wide circuit made to avoid them. We did not leave the road, as there was no road to leave. The compass directed our course, and the driver steered us, and believe me, careful steering was required. In the wooded country the boughs of the trees were so thick and low, that often the wagon could not pass under them, and the way had to be cleared with the axe; more than once a fresh route had to be chosen. Then there were also fallen trees to be avoided. In the open country numberless holes made by the meerkat, a little burrowing creature, and the larger holes of jackals and wolves, were a source of danger, especially when hidden by long grass; last but not least, the innumerable antheaps, varying in height from a few inches to several feet, were so close together, that it was impossible to miss them and many a tremendous jolt did they give us. Yet never once was the wagon capsized.

One evening at dusk, my Father was looking out for a suitable place to spend the night; we children were tired and wanted our supper, and seeing a large tree near, begged him to stop by it; but he preferred another tree with less undergrowth, some yards further on, so there we outspanned. Soon a large fire was burning, and we were seated round it; all about us was the dark forest, and above the sky, bright with stars; preparations for supper were going forward; from the frying pan over the fire came the delicious odour of venison steaks, sharpening the appetite; the children were talking and laughing merrily, and all was peace and content. Suddenly from the tree which we had passed, came a loud, terrible howl, and a large wolf sprang out, and rushed away into the darkness. The smell of the venison had reached his nostrils, and wakened him as he lay in his den, but the sight of the fire was too much for him, and he fled. We were much alarmed as you may suppose, and frightened crying took the place of merry laughter; but soon our fears were calmed, and quiet restored.

My father was no sportsman, and used his gun only to keep up the supply of fresh meat; he was not a good marksman either, and if game had not been so plentiful that it was difficult to miss, we might have fared badly. The supply of meat was running short one day, when buffalo were sighted, they were feeding on open ground, whilst our wagon was among bush. Taking his gun, my Father set off to try for one; he had not attempted such large game before. On getting within range, he fired and one buffalo dropped, and lay as though dead; the rest of the herd galloped off. My father approached the animal slowly, preparing his gun for another charge, though it seemed needless. I should tell you that it was one of those old fashioned guns which were loaded through the muzzle with a ramrod - a very slow process. Before he could load the gun, the buffalo suddenly sprang up, and danced round in circles; then catching sight of my father, it made a dash for him. He turned and ran, hoping to gain the shelter of the bush, for a wounded buffalo is a dangerous foe; the buffalo gained rapidly, and the chance of escape seemed almost gone, when suddenly the animal wheeled round and galloped after its companions. Most of this scene was visible from the wagon, and my mother's excitement and anxiety were naturally very great, till she was assured of her husband's safety.

At a place called Lotlakana, (little need) the natives had been rendered very wild and suspicious by Boer raiders, who had kidnapped their children, and when our wagon was observed they hid their children. Here the first signs of superstition were seen. The wagon was outspanned near the river, for Sunday's rest, in the morning the girls came down to draw water, but before doing so they lay down, and wetted their stomachs with water, using incantations; this was for the purpose of counteracting any witchcraft which the missionary might have used to kidnap them. Before the day was over, however, my father had gained their confidence, and they gathered together to hear the gospel.

Next evening we reached Mafiking; this was not the chief's town in those days, but it was full of interest to the missionary, for here he found a chapel of burnt brick, built by a wandering German, and paid for the native teacher and people; when well filled it held 70. This native teacher was a brother of the chief Montsioa; his name was Molema. When a young man he took a journey of over 300 miles to Thaba 'Nchu, to hear the gospel, and was converted under the Rev Jno. Edwards. He went into school among the children, soon learned to read, and then returned to preach to his own people. This was about the year 1830, while Dr. Livingstone was still at Kolobeng, so that Molema was now an elderly man. He was the first native teacher to carry the gospel to his people.

Leaving Mafiking the journey was continued, and four days later Moshaneng was reached. Some time before, Montsioa had been driven from his country by the Boers, and had taken refuge with the Bangwaketse (people of the crocodile); they gave him the place called Moshaneng, which means 'in the morning'; it was about 12 miles west of their own chief town, Kanye. Here he lived a long time, waiting for an opportunity to return to his own country.

On our arrival at Moshaneng a native hut was lent us; it was a very poor one - the centre pole was decayed, and big hairy caterpillars used to drop down from it. Here we stayed a month, my father teaching and preaching. We found about 60 members under the care of native leaders. These leaders had been converted under Molema, had followed their chief when he fled, and had carried on the work. My mother was seized with a severe attack of fever, and in that poor hut she lay for days, with her life in danger. A trader in the neighbourhood was able to supply quinine, and under God's blessing she recovered. Thankful indeed were my parents for the presence of my aunt. She used to teach us part of every day, and take us out for walks.

One day I was left behind as a punishment, with a lesson to learn. Having finished the task and feeling lonely, I set out alone to meet the others. Half way down the long slope which led to the stream, a native man stopped me, and asked where I was going. I could speak Sechuana quite well, and answered him readily. He looked all round, but no one was in sight. 'You must not go further alone', he said, ' down there', pointing to the river, ' lives a big wolf, and he might catch you!' Thoroughly frightened, I began to cry, so he took my hand and led me back to the hut, and, with another kindly warning went his way. What he said was quite true; we heard the howling of that wolf many a night, and several times he came prowling near our hut. They are cowardly creatures and though they would seize a solitary child, would fear to attack a grown person.

The return journey was made towards the end of the dry season, and water was very scarce. Then was often seen that illusion called a 'mirage'; as the oxen crawled slowly over the dry, dusty country, there would appear before us as it were lakes of water, with trees and islands; the trees were often real enough but the water vanished as the spot was approached. On one occasion the oxen had been two days without water, and the supply in the barrels was very low; anxious eyes scanned the country eagerly for signs of water, and in the afternoon what appeared to be two large pools of water were seen at no great distance. A halt was made, and my father proceeded to the place saying 'That is no mirage!' He was right, but none the less, he met with a severe disappointment, for on reaching the spot he found two large salt-pans; the water had all dried up, leaving a deposit of salt on the surface, which, in the distance, looked like water. All about were spoor, or footprints, of wild animals, even of lions. Again the weary oxen moved on, distressed with thirst. As evening came on, to the great joy of all, water was found sufficient for all needs. Such salt pans as I have mentioned are common in those parts - in summer they are shallow lakes - in winter they usually dry up. There is large salt pan near Bloemhof which was profitably worked, and yielded a good supply of salt annually. Such were some of the events of that journey - in due time Thaba 'Nchu was reached, and ordinary life resumed.

Nearly two years later, my father again visited Moshaneng, and that time he went alone. A week or so earlier my mother and her children had started on a long journey south, to Grahamstown, with the intention of leaving my elder sister and myself with our relatives there to be educated. This was done, and nearly 7 years parents and children were entirely separated. Many missionaries have to undergo a similar trial in order that their children may be educated.

My mother arrived at Thaba 'Nchu about the same time as my father returned from his lonely journey. The report he brought was so satisfactory that the Society decided to establish a mission at Moshaneng, and my father being already known to the people was chosen for the work of Pioneer Missionary; he was the first European to live there. Many were the hardships and difficulties which they had to encounter. Their first home was two Kafir huts place side by side; they have no windows, the light can only enter by the low door. The three children took measles; the cases were slight and they were allowed to dress, but were kept in one hut. In the other but lay my mother, unable to stand on her feet, or give any help. My father and a little native maid had to do everything for them.

On the many journeys which had to be taken among the surrounding towns and villages, it was often impossible for my mother to go, and she would be alone on the station with the children for 2 and 3 weeks at a time, sometimes longer.

The missionary needed some knowledge of medicine, for the people came to him with their sicknesses; the worse the dose administered the more efficacious they thought it. One old man was very troublesome; he was always coming for medicine, and there was nothing the matter with him, so one day my father gave him a special pill - it was composed of bitter aloes, asafoetida and one or two other things - of that sort, made into a pill with soap. This he was told to chew slowly, and being watched all the while, he obeyed. It cured him!

Anyone who knows mosquitoes would consider them a strange instrument to be used in saving life. Yet they did this great service once. When returning from the District Meeting one year, the Bet river was reached in the evening. The river seemed passable, and in the rainy season the rule is - cross a river as soon as you come to it, if it is passable, and outspan on the other side. But this drift or ford was too dangerous to be attempted in the dark, so the wagon was outspanned in what seemed a safe place. No sooner was the lantern lit, than the mosquitos began to swarm into the wagon, stinging everybody. The lantern was put out, the sail let down in front, but all to no purpose, - even the oxen grew restless, and it was evident that neither supper nor sleep could be obtained in that spot. Orders were given to inspan again and move to higher ground; this was done, and not another mosquito was heard that night!

When they rose early in the morning, what a sight met their eyes! The river had come down in the night and flooded the country far on either side, and the spot from which the mosquitoes had driven the wagon was now deep under water. Near was a Boer homestead, a very poor place, but the people were kind hearted, and did what little lay in their power for the travellers; the wagon was drawn up close to the house and there they waited for six weeks before the river again became passable.

When Montsioa was trying to obtain British protection that he might return to his country, he desired my father, in whom he had great confidence, to accompany him when he visited the Governor, and to speak for him. The result of that meeting and others which followed was that Bechuanaland was taken under British protection. Montsioa then returned to his own country and finally settled in Mafikeng, making it his chief town. The name of this place is both mis-spelt and mis-pronounced now a days - the Sechuana word is 'Mafikeng' not 'Mafeking' It means the place of the Rocks. When the chief and his people removed, it became necessary for the missionary to move also; so my father settled among them at Mafiking. During the years he laboured among them, the work prospered, and 100 members were added to the 60 he found there.

In telling you this story, my hope is that it may awaken in you a stronger and more active sympathy with our Missionaries. Try to realize their life on those far away stations - the loneliness - for months, even years, elapsed without the sight of a white face; the longing for sympathy - for someone to talk to, especially in time of sickness. Think of the privations which they endured. In summer fresh meat was seldom obtainable, and the supply of fowls and eggs very irregular and poor. In winter there was no butter and often no milk; while sugar and other groceries had to be most carefully and sparingly used lest the supply should fail before more could be obtained. Once this happened, and a terribly hard time it was for them all, my father had to take a long and arduous journey to Kimberley, 250 miles, to get the necessaries of life.

Think of all this, and compare it with your comfortable homes, and own lives. How much have you sacrificed that the heathen may have the gospel preached to them? When you are about to indulge in some luxury, think of the self-denial practised by some of your fellow christians, and ask yourself whether it would not be better for you to give the money to Christ, even thought the amount be small, rather than to spend i on yourself. Put it in the missionary box, and when you have done this a few times you will begin to realise the blessedness of giving, for Jesus himself said 'It is more blessed to give than to receive'.